You hear about it all the time: How so-and-so used to ride with him, but now she’s riding with her. How Up-and-Coming-Rider left Fancy-Trainer-One’s barn and is now working with Fancy-Trainer-Two. How your friend used to go to all of that horseman’s clinics, but now she goes to all this horseman’s clinics.

Riders notoriously have a wandering eye–admit it, most of us at one time or another thought someone else could help us reach our equestrian goals a little bit sooner…or had a disagreement that felt like a deal-breaker and sent us scouring trainer websites in search of the one who is really, truly, our perfect match. The thing is, riding with a coach or instructor is a relationship like any other, and sure to come with its arguments, frustrations, and boring bits. The trick is knowing when you just need to work a little harder at it, and when it is time to call it a day.

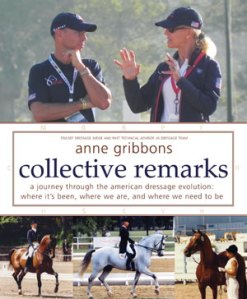

In COLLECTIVE REMARKS: A JOURNEY THROUGH THE AMERICAN DRESSAGE EVOLUTION, FEI/USEF judge and former technical advisor to the US Dressage Team Anne Gribbons discusses the ins and outs of rider-coach matchmaking…and how to tame that wandering eye.

The Problem with “Teacher-Hopping”

If you manage to locate an instructor who is a wonderful rider and who also has the ability to make you understand how to accomplish your goals, you can “have your cake and eat it, too.” In the case when you cannot have it all, you are definitely better off with the competent teacher than with the “big name” who cannot teach. Unless you are a person who can learn by watching and has years to spend doing it, you need someone who can explain why and how to make you and your horse perform.

Your first dressage instructor is likely to become the most profound influence on your riding because he or she will responsible for laying the foundation of your riding and creating your “basic system.” The longer you spend with this teacher, the firmer your base, upon which you will later build by receiving additional help and advice from other sources. The lack of a basic system is one of the problems in American dressage, created by a tendency to enjoy a “smorgasbord education”: The minute something goes wrong in training we look for another instructor, and of course we also have to ride in every clinic offered within reach. God forbid we miss any of the action!

For the novice rider, “teacher-hopping” is confusing at best and damaging at worst, and for the horse it will eventually prove detrimental. A horse cannot absorb and adjust to a different method of training every two weeks without losing his confidence and perhaps his mind, as well. It does not matter if the various clinicians the novice works with are all excellent trainers, they are still not going to teach exactly the same way, and at this stage, more is not better. It takes many years of training and riding before a rider can truly profit from a clinic by incorporating the useful parts into his or her program while discarding the ideas that do not work for the horse. You have to be experienced enough to know the difference. The best way to make use of clinics while you are still a novice is to attend tas an auditor, then discuss the experience with your regular instructor, and perhaps try some of the ideas you are interested in during a lesson.

A Healthy Relationship

To get the most out of your relationship with an instructor it is important that there is a mutual feeling of commitment, respect, and trust. A teacher shows his or her commitment, first and foremost, by giving exclusive attention to the student who is paying for the lesson. Conversations on the side and phone calls with others should be avoided if possible. This applies also to a clinic situation, when the temptation of playing to the audience at the expense of the student may be great. At shows the serious instructor is available to school and advise the student before each ride, and will observe the ride and comment on it afterward. For a teacher with many students at the show, this may be impossible due to conflicting ride times, but a schedule can be made up ahead that divides his or her time and gives everyone an opportunity to get some help. However the test goes, a teacher of the right kind stands by his or her student in tragedy as well as triumph, and all post-test corrections and negative criticism that may be necessary are done one on one. A respectful instructor does not harass, make fun of, or belittle a student, never mind how frustrating the lesson or situation may be. There are times when a harsh command—even screaming—is called for, because the student is not reacting fast enough, but if the rider does not understand the command, raising the volume creates nothing but tension and further confusion.

The student has responsibilities as well. The first and perhaps most important is to shut up and ride! A lesson is no time for dialogue, and it is incredibly irritating to have someone contradicting every order or constantly explaining why whatever you ask for cannot be done. This kind of behavior also interferes with the flow of information between the horse and the rider, since the horse senses that the rider is not tuned in to the effort. Questions and explanations should wait until a break or rest period, unless there is some emergency the instructor needs to be made aware of. Complete concentration throughout the lesson, a commitment to practicing what is being taught (even outside of the teaching sessions), and consistency in pursuing the lesson program are all virtues belonging to the “good student.”

When to Move On

There may come a time after a long relationship when the student feels there is no progress being made. Before placing the blame on the teacher (always the easy out), take a long hard look at yourself and ask: “How talented, how persistent, and how hard-working am I as a student?” And, “Do I have the right ‘vehicle,’ or is my horse not right for the job?” If, after some soul-searching, you are absolutely certain that the problem is not of your own making, talk to your instructor. There may well be a mutual feeling of frustration and stagnation. If the problems cannot be worked out and you decide to look for help elsewhere, you owe it to your present instructor to inform him or her about your decision, before he or she hears it from somebody else.

Wherever you go with your riding, remember, when success comes your way, give credit to each person who contributed to your progress. Not just the famous “final polisher” of your now wonderful self, but also the people who put up with you when you and everybody else thought you were hopeless!

Read more humorous insight from Anne Gribbons in COLLECTIVE REMARKS, available from the TSB online bookstore, where shipping in the US is FREE.

CLICK HERE to download a free chapter or to order.

Trafalgar Square Books, the leading publisher of equestrian books and DVDs, is a small business based on a farm in rural Vermont.